George Orwell’s Animal Farm, first published in 1945, remains one of the most powerful political allegories ever written. Though it appears at first to be a simple fable about farm animals rebelling against their human owner, beneath its surface lies a sharp critique of totalitarianism, propaganda, and the corrupting nature of power. Decades later, this short novel continues to resonate with readers, scholars, and political observers around the world.

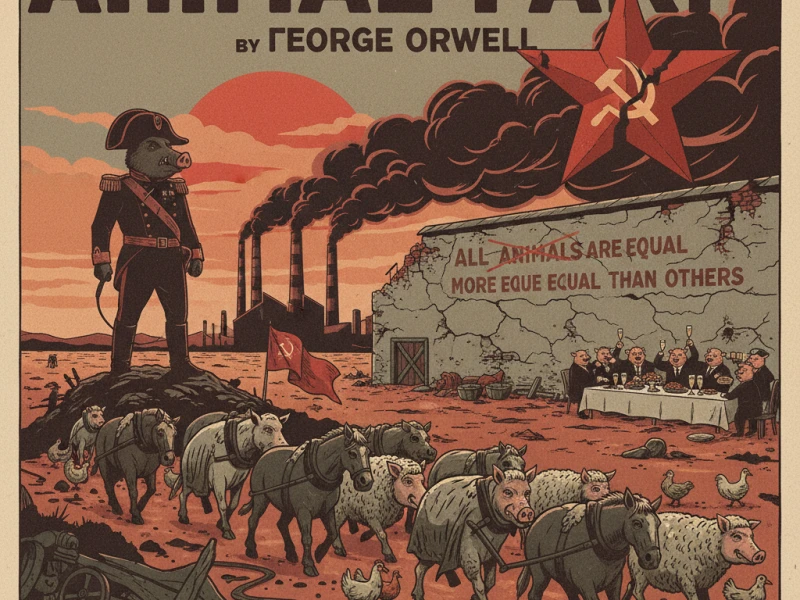

The story begins at Manor Farm, where the animals, tired of exploitation under their human master Mr. Jones, rise up in a revolution inspired by the dream of freedom and equality. Led initially by the pigs Snowball and Napoleon, the animals establish a new order based on the principles of Animalism: “All animals are equal.” Hopeful and spirited, they work together to build a fair society where no creature suffers at the hands of another.

But as the narrative unfolds, Orwell masterfully demonstrates how ideals can be twisted and corrupted. Napoleon, the ambitious pig, gradually seizes control, sidelining Snowball and turning Animal Farm into a dictatorship that eerily mirrors the tyranny the animals once overthrew.

Through subtle manipulations of language, propaganda by the pig Squealer, and ruthless violence by the dogs, Napoleon consolidates power while the rest of the animals toil harder than ever. The commandments of Animalism are altered to suit the ruling class, until the famous line shifts from “All animals are equal” to the chilling conclusion: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

What makes Animal Farm so enduring is Orwell’s ability to blend simplicity with depth. The narrative is accessible even to younger readers, yet the allegory offers layers of meaning for adults.

Each character represents figures from Soviet history—Napoleon as Joseph Stalin, Snowball as Leon Trotsky, and Boxer the horse symbolizing the exploited working class.

Yet the novel is not confined to one historical context; it transcends time and geography. Any society where power becomes concentrated in the hands of a few, where truth is manipulated, and where ordinary people are oppressed can see itself reflected in Orwell’s farmyard mirror.

Orwell’s prose is crisp and unadorned, which adds to the story’s impact. His restraint allows the events and symbolism to speak for themselves. The fable format also makes the satire biting without being heavy-handed. The novel’s brevity—barely over 100 pages—ensures that every line matters, and the pacing drives the reader toward its stark conclusion with unsettling inevitability.

Beyond its political allegory, Animal Farm raises universal questions: Can revolutions ever fulfill their promise? Do power and corruption always go hand in hand? Is equality possible in human—or animal—society? These questions give the book its timelessness, making it as relevant in the 21st century as it was in Orwell’s own turbulent era.

Ultimately, Animal Farm is more than a critique of Soviet communism; it is a warning about the fragility of freedom and the dangers of unchecked authority. It reminds us that vigilance, critical thinking, and accountability are essential to prevent history’s darker cycles from repeating. For anyone seeking to understand the dynamics of power, ideology, and resistance, Orwell’s classic remains essential reading.

Prev Post :

Prev Post :